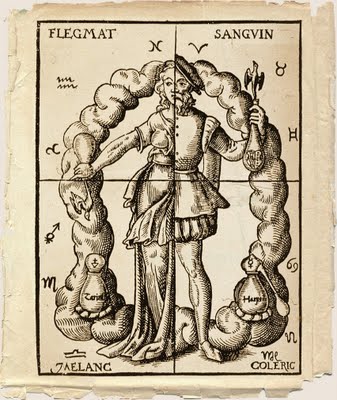

Antebellum health care was, in comparison to today’s modern scientific discoveries, rather unsophisticated. Most health care professionals still adhered to the Hippocratic Theory of the Four Humors, which claimed that disease or sickness happened to a person when their humors were out of balance and the best treatment usually involved purging the body by way of bleeding, sweating, or vomiting. Usually, those who fell ill were treated in their own home rather than at hospitals, thus giving them a predisposition towards self-care – the practice of “personal hygiene, supplementing one’s diet with fruits and vegetables, exercising regularly, protecting oneself from the elements, eradicating pests, and consistently communicating with loved ones.” (177).

Kathryn Meier addresses the issue of self-care and the effect of the environment on soldiers in their article “No Place for the Sick”. The Peninsula and Shenandoah Valley Campaigns exposed soldiers to an environment which many of them had never experienced before. In general, the South was regarded as sickly due to a harsh, rural environment filled with swamp, insects, and bacteria. Soldiers did recognize a relationship between their environment and their physical and mental health, and believed their “exposure….to inclement weather, roily water, dangerous ‘airs’…a new climate, harsh seasonal changes, and pests” were the reasons for their physical and mental ailments. Exposure to these threats was believed to be the cause for physical sickness, while inclement weather was usually linked to poor mental state (178). Physical and mental health were “very much interrelated in Civil War soldier experience”, for those who were often physically sick fell into a state of melancholy. Surgeon Alfred L. Castleman drew a correlation between positive mental attitudes and physical health by claiming that “nine causes out of ten whenever a sick soldier yielded to the idea that he would not recover, he would certainly die” (179).

Despite a slight improvement in medicine during the war, partly due to the efforts of the U.S. Sanitary Commission and the sanitation movement, the field healthcare infrastructure of both the Union and the Confederacy were weak and generally unreliable, further pushing soldiers to a policy of self-care. Men had to learn how to take care of each other, for their traditional female caretakers were not available to them on the battlefield. According to Meier, the decision to adhere to self-care “was far more important to overall health than where [an individual] was stationed” (178). The process of

“THE SURGEON AT WORK AT THE REAR DURING AN ENGAGEMENT” Winslow Homer (Harper’s Weekly: July 12, 1862, p. 439)

decisions made by soldiers in the field is known as “seasoning”. During this time, soldiers adapted to their surroundings, and often depended on and helped each other stay healthy. This dependency on comrades came from the sense of dread a man felt when condemned to the field hospital. Hospitals gave preference to the wounded, and care for the sick was seen as impersonal and neglectful – a long shot from the home-care they were used to and the self-care they adhered to.

What I found particularly interesting was Meier’s section on the impact of battlefields on soldiers’ mental health. The sight of hundreds of dead bodies caused mental anguish, but the thought of death in battle “was preferable to death by disease”. Perishing from a disease “[robbed] the men of a chance to fulfill their sense of duty” (184). Thus, soldiers who were more aware of their environment and who practiced self-care were less likely to succumb to disease and were therefore “more valuable to the cause” (200). In order to be useful in battle, a solider had to be in good health. Otherwise, he would not be able to fully dedicate himself to battle.